The Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in architecture, mathematics, astronomy, and art, flourished in Mesoamerica for over three millennia. From around 2000 BCE to the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, the Maya developed a highly sophisticated society with unique cultural and scientific contributions that continue to intrigue historians and archaeologists to this day (Coe & Houston, 2015). Are you ready to discover more about the Maya civilization?

Origins and Early Development

The roots of Maya civilization can be traced back to the pre-classic period, around 2000 BCE, when early agricultural communities began to emerge in what is now southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (Sharer & Traxler, 2006). The shift from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to settled farming communities was marked by the cultivation of maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers. These staple crops formed the foundation of the Maya diet and allowed for the growth of complex societies (Rice, 2009).

Classic Period: A Time of Flourishing

The Classic Period (250–900 CE) is often hailed as the golden age of Maya civilization, marked by remarkable cultural achievements. During this era, the Maya built impressive cities like Tikal and Palenque, with towering pyramids, grand palaces, and intricately decorated temples (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

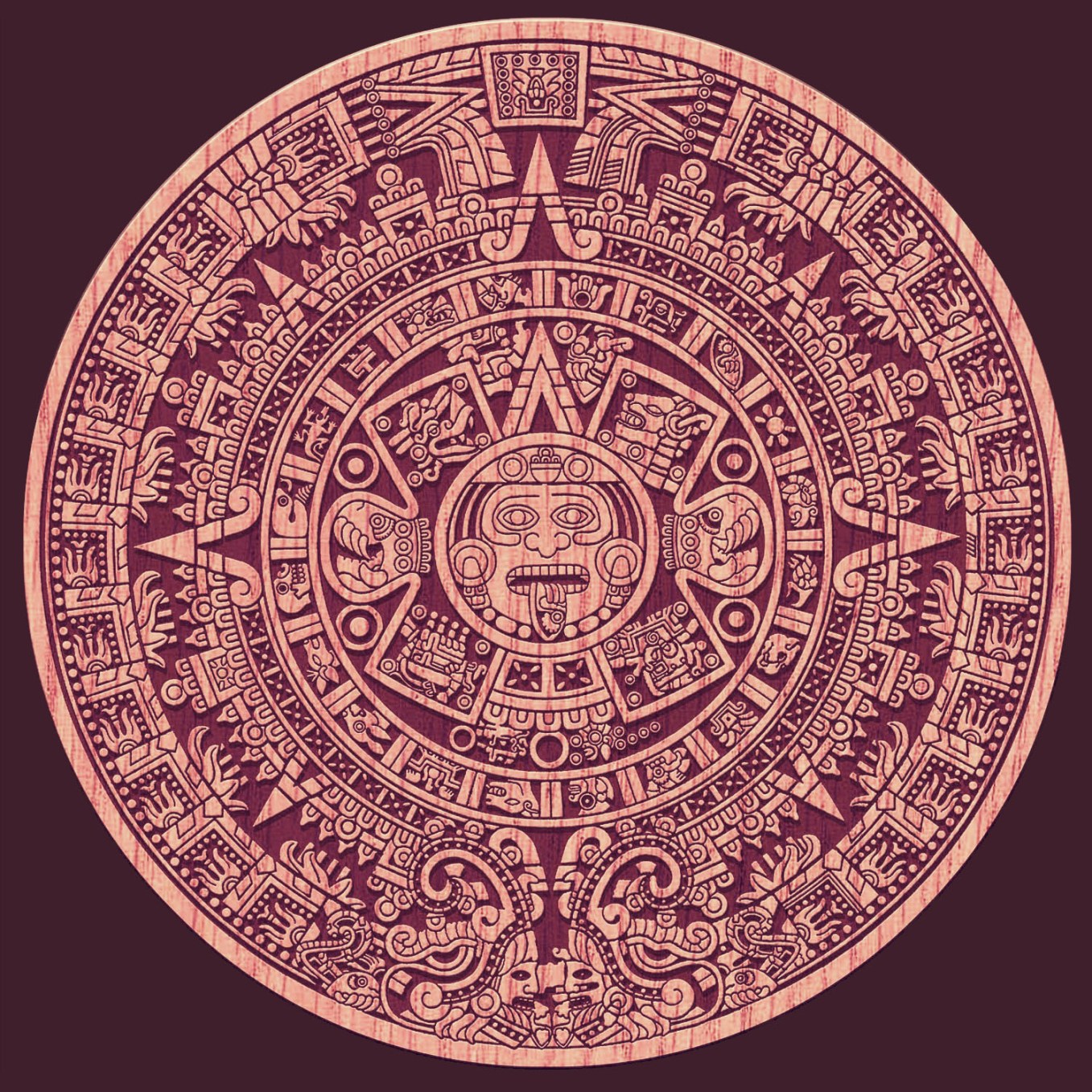

The Maya also developed a sophisticated writing system consisting of over 800 glyphs, which they used to record historical events, astronomical observations, and religious texts. Their advances in mathematics, including the concept of zero and a base-20 numbering system, enabled them to create precise calendars and predict astronomical events (Rice, 2009).

Politically, the Maya were organized into independent city-states, each ruled by a king or queen. These rulers were seen as divine intermediaries and legitimized their power through elaborate rituals and monumental architecture (Hansen, 2001).

Architectural Marvels

The cities of the Classic Period, such as Tikal, Palenque, Copán, and Calakmul, are renowned for their grandiose architecture. The Maya constructed towering pyramids, elaborate temples, and expansive palaces, often adorned with intricate carvings and stucco reliefs. The pyramid of El Castillo at Chichen Itza and the Temple of the Great Jaguar at Tikal are just two examples of their architectural prowess (Coe & Houston, 2015).

Writing and Mathematics

The Maya developed one of the most advanced writing systems in pre-Columbian America, consisting of over 800 glyphs representing words, syllables, and sounds. This script was used to record historical events, astronomical observations, and religious texts on stelae, pottery, and codices (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

In addition to their writing system, the Maya made remarkable strides in mathematics. They were among the first to use the concept of zero and developed a vigesimal (base-20) numbering system. This mathematical acumen enabled them to create complex calendars and accurately predict astronomical events (Rice, 2009).

Astronomical Achievements

Maya astronomers meticulously observed the movements of celestial bodies and developed highly accurate calendars. The 260-day Tzolk’in and the 365-day Haab’ calendars were used for agricultural, religious, and social purposes. The Long Count calendar, which tracks longer periods, was famously used to predict the end of a major cycle on December 21, 2012, leading to widespread speculation about the “Maya apocalypse” (Schele & Freidel, 1990).

Religion and Cosmology

Religion permeated every aspect of Maya life, with a pantheon of gods representing natural forces and celestial bodies. The Maya believed that the universe was divided into three realms: the heavens, the earthly world, and the underworld, known as Xibalba. Kings and priests served as intermediaries between the gods and the people, performing elaborate rituals and ceremonies to maintain cosmic harmony (Rice, 2009).

Sacred Cenotes

Cenotes, natural sinkholes filled with water, held significant religious importance for the Maya. They were believed to be portals to the underworld and were often used for ritual sacrifices. The Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, for example, was a site of pilgrimage and offerings, including precious items and human sacrifices (Schele & Freidel, 1990).

The Mysterious Collapse

Around the 9th century CE, many of the great Maya cities of the southern lowlands were abandoned, leading to what is known as the “Maya collapse.” The reasons for this decline are still debated, but theories include environmental degradation, prolonged drought, warfare, and internal social upheaval (Hansen, 2001). Despite the decline of the southern cities, the Maya civilization persisted in the northern Yucatán Peninsula, with cities like Chichen Itza and Uxmal continuing to thrive until the arrival of the Spanish (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

Legacy and Cultural Continuity

The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century marked the end of the Maya civilization as a dominant power, but their cultural legacy endures. Today, millions of people in Mesoamerica identify as Maya and continue to speak Maya languages, practice traditional crafts, and celebrate ancient customs (Coe & Houston, 2015). The rediscovery and study of Maya ruins have also contributed to a broader understanding and appreciation of their remarkable achievements (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

Modern Maya Communities

Modern Maya communities, such as those in Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, preserve many aspects of their ancestral heritage. Traditional clothing, weaving techniques, and rituals, such as the Day of the Dead and the festival of the Rain God Chaac, are integral to contemporary Maya life. Efforts to revive the Maya script and preserve oral histories further underscore the resilience and continuity of Maya culture (Rice, 2009).

References

Coe, M. D., & Houston, S. (2015). The Maya (9th ed.). Thames & Hudson.

Sharer, R. J., & Traxler, L. P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford University Press.

Schele, L., & Freidel, D. (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. William Morrow.

Rice, P. M. (2009). Maya Political Science: Time, Astronomy, and the Cosmos. University of Texas Press.

Hansen, R. D. (2001). The Architectural Dynamics of Maya Civilization: Political Innovation, Classic Period Change, and Terminal Classic Collapse. Journal of Archaeological Research, 9(4), 369-407.